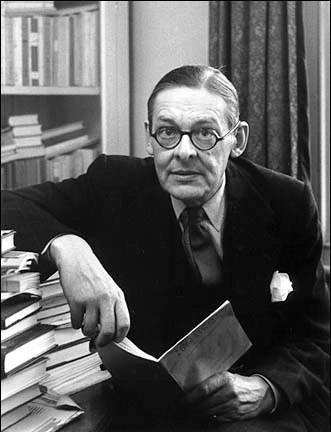

Eliot, T. S.: The Waste Land

The Waste Land (Angol)"Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Sibylla ti theleis; respondebat illa: apothanein thelo."

"For I myself saw the Sibyl indeed at Cumae with my own eyes hanging in a jar; and when the boys used to say to her, "Sibyl, what do you want?" she replied, 'I want to die."

The epigraph is taken from Chapter 48 of the Satyricon written by Gaius Petronius Arbiter (or Titus Petronius).

For Ezra Pound: il miglior fabbro

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain. Winter kept us warm, covering 5 Earth in forgetful snow, feeding A little life with dried tubers. Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade, And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, 10 And drank coffee, and talked for an hour. Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch. And when we were children, staying at the archduke's, My cousin's, he took me out on a sled, And I was frightened. He said, Marie, 15 Marie, hold on tight. And down we went. In the mountains, there you feel free. I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, 20 You cannot say, or guess, for you know only A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, And the dry stone no sound of water. Only There is shadow under this red rock, 25 (Come in under the shadow of this red rock), And I will show you something different from either Your shadow at morning striding behind you Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; I will show you fear in a handful of dust. 30 Frisch weht der Wind Der Heimat zu. Mein Irisch Kind, Wo weilest du? 'You gave me hyacinths first a year ago; 35 'They called me the hyacinth girl.' —Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden, Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither Living nor dead, and I knew nothing, 40 Looking into the heart of light, the silence. Od' und leer das Meer.

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante, Had a bad cold, nevertheless Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe, 45 With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she, Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor, (Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!) Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks, The lady of situations. 50 Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel, And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card, Which is blank, is something he carries on his back, Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find The Hanged Man. Fear death by water. 55 I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring. Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone, Tell her I bring the horoscope myself: One must be so careful these days.

Unreal City, 60 Under the brown fog of a winter dawn, A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, I had not thought death had undone so many. Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled, And each man fixed his eyes before his feet. 65 Flowed up the hill and down King William Street, To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine. There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying 'Stetson! 'You who were with me in the ships at Mylae! 70 'That corpse you planted last year in your garden, 'Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year? 'Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed? 'Oh keep the Dog far hence, that's friend to men, 'Or with his nails he'll dig it up again! 75 'You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!'

II. A Game of Chess

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne, Glowed on the marble, where the glass Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines From which a golden Cupidon peeped out 80 (Another hid his eyes behind his wing) Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra Reflecting light upon the table as The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it, From satin cases poured in rich profusion; 85 In vials of ivory and coloured glass Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes, Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air That freshened from the window, these ascended 90 In fattening the prolonged candle-flames, Flung their smoke into the laquearia, Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling. Huge sea-wood fed with copper Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone, 95 In which sad light a carvèd dolphin swam. Above the antique mantel was displayed As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene The change of Philomel, by the barbarous king So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale 100 Filled all the desert with inviolable voice And still she cried, and still the world pursues, 'Jug Jug' to dirty ears. And other withered stumps of time Were told upon the walls; staring forms 105 Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed. Footsteps shuffled on the stair. Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair Spread out in fiery points Glowed into words, then would be savagely still. 110

'My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me. 'Speak to me. Why do you never speak? Speak. 'What are you thinking of? What thinking? What? 'I never know what you are thinking. Think.'

I think we are in rats' alley 115 Where the dead men lost their bones.

'What is that noise?' The wind under the door. 'What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?' Nothing again nothing. 120 'Do 'You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember 'Nothing?' I remember Those are pearls that were his eyes. 125 'Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?' But O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag— It's so elegant So intelligent 130 'What shall I do now? What shall I do?' 'I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street 'With my hair down, so. What shall we do to-morrow? 'What shall we ever do?' The hot water at ten. 135 And if it rains, a closed car at four. And we shall play a game of chess, Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door.

When Lil's husband got demobbed, I said— I didn't mince my words, I said to her myself, 140 HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME Now Albert's coming back, make yourself a bit smart. He'll want to know what you done with that money he gave you To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there. You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set, 145 He said, I swear, I can't bear to look at you. And no more can't I, I said, and think of poor Albert, He's been in the army four years, he wants a good time, And if you don't give it him, there's others will, I said. Oh is there, she said. Something o' that, I said. 150 Then I'll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look. HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME If you don't like it you can get on with it, I said. Others can pick and choose if you can't. But if Albert makes off, it won't be for lack of telling. 155 You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique. (And her only thirty-one.) I can't help it, she said, pulling a long face, It's them pills I took, to bring it off, she said. (She's had five already, and nearly died of young George.) 160 The chemist said it would be alright, but I've never been the same. You are a proper fool, I said. Well, if Albert won't leave you alone, there it is, I said, What you get married for if you don't want children? HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME 165 Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon, And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot— HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight. 170 Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight. Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

III. The Fire Sermon

The river's tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed. 175 Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song. The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers, Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed. And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors; 180 Departed, have left no addresses. By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept... Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song, Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long. But at my back in a cold blast I hear 185 The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear. A rat crept softly through the vegetation Dragging its slimy belly on the bank While I was fishing in the dull canal On a winter evening round behind the gashouse 190 Musing upon the king my brother's wreck And on the king my father's death before him. White bodies naked on the low damp ground And bones cast in a little low dry garret, Rattled by the rat's foot only, year to year. 195 But at my back from time to time I hear The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring. O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter And on her daughter 200 They wash their feet in soda water Et, O ces voix d'enfants, chantant dans la coupole!

Twit twit twit Jug jug jug jug jug jug So rudely forc'd. 205 Tereu

Unreal City Under the brown fog of a winter noon Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants 210 C.i.f. London: documents at sight, Asked me in demotic French To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel Followed by a weekend at the Metropole.

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back 215 Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits Like a taxi throbbing waiting, I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives, Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives 220 Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea, The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights Her stove, and lays out food in tins. Out of the window perilously spread Her drying combinations touched by the sun's last rays, 225 On the divan are piled (at night her bed) Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays. I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest— I too awaited the expected guest. 230 He, the young man carbuncular, arrives, A small house agent's clerk, with one bold stare, One of the low on whom assurance sits As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire. The time is now propitious, as he guesses, 235 The meal is ended, she is bored and tired, Endeavours to engage her in caresses Which still are unreproved, if undesired. Flushed and decided, he assaults at once; Exploring hands encounter no defence; 240 His vanity requires no response, And makes a welcome of indifference. (And I Tiresias have foresuffered all Enacted on this same divan or bed; I who have sat by Thebes below the wall 245 And walked among the lowest of the dead.) Bestows on final patronising kiss, And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit...

She turns and looks a moment in the glass, Hardly aware of her departed lover; 250 Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass: 'Well now that's done: and I'm glad it's over.' When lovely woman stoops to folly and Paces about her room again, alone, She smoothes her hair with automatic hand, 255 And puts a record on the gramophone.

'This music crept by me upon the waters' And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street. O City city, I can sometimes hear Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street, 260 The pleasant whining of a mandoline And a clatter and a chatter from within Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls Of Magnus Martyr hold Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold. 265

The river sweats Oil and tar The barges drift With the turning tide Red sails 270 Wide To leeward, swing on the heavy spar. The barges wash Drifting logs Down Greenwich reach 275 Past the Isle of Dogs. Weialala leia Wallala leialala

Elizabeth and Leicester Beating oars 280 The stern was formed A gilded shell Red and gold The brisk swell Rippled both shores 285 Southwest wind Carried down stream The peal of bells White towers Weialala leia 290 Wallala leialala

'Trams and dusty trees. Highbury bore me. Richmond and Kew Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe.' 295 'My feet are at Moorgate, and my heart Under my feet. After the event He wept. He promised "a new start". I made no comment. What should I resent?' 'On Margate Sands. 300 I can connect Nothing with nothing. The broken fingernails of dirty hands. My people humble people who expect Nothing.' 305 la la

To Carthage then I came

Burning burning burning burning O Lord Thou pluckest me out O Lord Thou pluckest 310

burning

IV. Death by Water

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead, Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep seas swell And the profit and loss. A current under sea 315 Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell He passed the stages of his age and youth Entering the whirlpool. Gentile or Jew O you who turn the wheel and look to windward, 320 Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

V. What the Thunder said

After the torchlight red on sweaty faces After the frosty silence in the gardens After the agony in stony places The shouting and the crying 325 Prison and place and reverberation Of thunder of spring over distant mountains He who was living is now dead We who were living are now dying With a little patience 330

Here is no water but only rock Rock and no water and the sandy road The road winding above among the mountains Which are mountains of rock without water If there were water we should stop and drink 335 Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand If there were only water amongst the rock Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit 340 There is not even silence in the mountains But dry sterile thunder without rain There is not even solitude in the mountains But red sullen faces sneer and snarl From doors of mudcracked houses If there were water 345 And no rock If there were rock And also water And water A spring 350 A pool among the rock If there were the sound of water only Not the cicada And dry grass singing But sound of water over a rock 355 Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop But there is no water

Who is the third who walks always beside you? When I count, there are only you and I together 360 But when I look ahead up the white road There is always another one walking beside you Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded I do not know whether a man or a woman —But who is that on the other side of you? 365

What is that sound high in the air Murmur of maternal lamentation Who are those hooded hordes swarming Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth Ringed by the flat horizon only 370 What is the city over the mountains Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air Falling towers Jerusalem Athens Alexandria Vienna London 375 Unreal

A woman drew her long black hair out tight And fiddled whisper music on those strings And bats with baby faces in the violet light Whistled, and beat their wings 380 And crawled head downward down a blackened wall And upside down in air were towers Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

In this decayed hole among the mountains 385 In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel There is the empty chapel, only the wind's home. It has no windows, and the door swings, Dry bones can harm no one. 390 Only a cock stood on the rooftree Co co rico co co rico In a flash of lightning. Then a damp gust Bringing rain

Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves 395 Waited for rain, while the black clouds Gathered far distant, over Himavant. The jungle crouched, humped in silence. Then spoke the thunder D A 400 Datta: what have we given? My friend, blood shaking my heart The awful daring of a moment's surrender Which an age of prudence can never retract By this, and this only, we have existed 405 Which is not to be found in our obituaries Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor In our empty rooms D A 410 Dayadhvam: I have heard the key Turn in the door once and turn once only We think of the key, each in his prison Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours 415 Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus D A Damyata: The boat responded Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar The sea was calm, your heart would have responded 420 Gaily, when invited, beating obedient To controlling hands

I sat upon the shore Fishing, with the arid plain behind me Shall I at least set my lands in order? 425

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s'ascose nel foco che gli affina Quando fiam ceu chelidon—O swallow swallow Le Prince d'Aquitaine à la tour abolie These fragments I have shored against my ruins 430 Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo's mad againe. Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih

T.S. Eliots Notes on the „Waste Land”

Not only the title, but the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L. Weston's book on the Grail legend: From Ritual to Romance (Cambridge). Indeed, so deeply am I indebted, Miss Weston's book will elucidate the difficulties of the poem much better than my notes can do; and I recommend it (apart from the great interest of the book itself) to any who think such elucidation of the poem worth the trouble. To another work of anthropology I am indebted in general, one which has influenced our generation profoundly; I mean The Golden Bough; I have used especially the two volumes Adonis, Attis, Osiris. Anyone who is acquainted with these Works will immediately recognise in the poem certain references to vegetation ceremonies.

I. The Burial of the Dead

Line 20. Cf. Ezekiel 2:1. 23. Cf. Ecclesiastes 12:5. 31. V. Tristan und Isolde, i, verses 5-8. 42. Id. iii, verse 24. 46. I am not familiar with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack 60. Cf. Baudelaire: "Fourmillante cite;, cite; pleine de reves, 63. Cf. Inferno, iii. 55-7. "si lunga tratta 64. Cf. Inferno, iv. 25-7: "Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare, 68. A phenomenon which I have often noticed. 74. Cf. the Dirge in Webster's White Devil . 76. V. Baudelaire, Preface to Fleurs du Mal.

II. A Game of Chess

77. Cf. Antony and Cleopatra, II. ii., l. 190. 92. Laquearia. V. Aeneid, I. 726: dependent lychni laquearibus aureis incensi, et noctem flammis 98. Sylvan scene. V. Milton, Paradise Lost, iv. 140. 99. V. Ovid, Metamorphoses, vi, Philomela. 100. Cf. Part III, l. 204. 115. Cf. Part III, l. 195. 118. Cf. Webster: "Is the wind in that door still?" 126. Cf. Part I, l. 37, 48. 138. Cf. the game of chess in Middleton's Women beware Women.

III. The Fire Sermon

176. V. Spenser, Prothalamion. 192. Cf. The Tempest, I. ii. 196. Cf. Marvell, To His Coy Mistress. 197. Cf. Day, Parliament of Bees: "When of the sudden, listening, you shall hear, 199. I do not know the origin of the ballad from which these lines 202. V. Verlaine, Parsifal. 210. The currants were quoted at a price "carriage and insurance Notes 196 and 197 were transposed in this and the Hogarth Press edition, 210. "Carriage and insurance free"] "cost, insurance and freight"-Editor. 218. Tiresias, although a mere spectator and not indeed a "character," '. . . Cum Iunone iocos et maior vestra profecto est 221. This may not appear as exact as Sappho's lines, but I had in mind 253. V. Goldsmith, the song in The Vicar of Wakefield. 257. V. The Tempest, as above. 264. The interior of St. Magnus Martyr is to my mind one of 266. The Song of the (three) Thames-daughters begins here. 279. V. Froude, Elizabeth, Vol. I, ch. iv, letter of De Quadra "In the afternoon we were in a barge, watching the games on the river. 293. Cf. Purgatorio, v. 133: "Ricorditi di me, che son la Pia; 307. V. St. Augustine's Confessions: "to Carthage then I came, 308. The complete text of the Buddha's Fire Sermon (which corresponds 309. From St. Augustine's Confessions again. The collocation

V. What the Thunder said

In the first part of Part V three themes are employed: 357. This is Turdus aonalaschkae pallasii, the hermit-thrush 360. The following lines were stimulated by the account of one 367-77. Cf. Hermann Hesse, Blick ins Chaos: "Schon ist halb Europa, schon ist zumindest der halbe Osten Europas auf dem 402. "Datta, dayadhvam, damyata" (Give, sympathize, 408. Cf. Webster, The White Devil, v. vi: ". . . they'll remarry 412. Cf. Inferno, xxxiii. 46: "ed io sentii chiavar l'uscio di sotto Also F. H. Bradley, Appearance and Reality, p. 346: "My external sensations are no less private to myself than are my 425. V. Weston, From Ritual to Romance; chapter on the Fisher King. 428. V. Purgatorio, xxvi. 148. "'Ara vos prec per aquella valor 429. V. Pervigilium Veneris. Cf. Philomela in Parts II and III. 432. V. Kyd's Spanish Tragedy. 434. Shantih. Repeated as here, a formal ending to an Upanishad.

|

Átokföldje (Magyar)"Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Sibylla ti theleis; respondebat illa: apothanein thelo."

"Mert Sibyllát viszont saját szememmel láttam Cumae-ben; egy üveggömbben lebegett, és mikor a gyerekek azt mondták neki: Sibylla, mit akarsz; azt felelte: Meg akarok halni."

Az epigraph forrása: Gaius Petronius Arbiter (vagy Titus Petronius) - Satyricon (XLVIII)

Ezra Poundnak a miglior fabbró-nak

I A halottak temetése

Április a kegyetlen, kihajtja Az orgonát a holt földből, beoltja Az emléket a vágyba, felkavarja Esőjével a tompa gyökeret. Tél melengetett minket, eltakarva Felejtő hóval a földet, kitartva Egy kis életet elszáradt gumókkal. Nyár tört ránk, átkelt a Starnbergersee-n Záporzuhogással; az oszlopok közt megálltunk, Napfényben elindultunk, a Hofgartenbe mentünk, 10 Kávéztunk s egy óráig társalogtunk. Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch. Kuzenom, a főherceg, amikor nála éltünk, Még gyerekkorunkban, szánkázni vitt, Én pedig féltem. Azt mondta, Marie, Marie, fogóddz. És szálltunk lefelé. A hegyek között, ott szabad az ember. Olvasni szoktam éjszaka s Délre utazni télen. Mi gyökerek kúsznak, mi ágazik szét E kő-szemétből? Embernek fia, 20 Nem mondhatod, nem sejted, mást sem ismersz, Csak egy csomó tört képet, ahol a tikkadt nap S a holt fa menhelyet nem ad, tücsök sem enyhülést, S a száraz kő se csörgedező vizet. Csupán E vörös szikla alatt van árnyék, (E vörös szikla alá jöjj, itt az árnyék), mutatok neked valamit, ami egészen más, Mint árnyad, amely reggel lép mögötted, Vagy árnyad, amely este kél előtted: Egy marék porban az iszonyatot megmutatom neked. 30

Frisch weht der Wind Der Heimat zu. Mein Irisch Kind, Wo weilest du?

„Egy éve adtál jácintot először: A jácintos lánynak neveztek el." — De mikor a Jácintkertből későn visszatértünk, Karod tele, hajad vizes, beszélni Se tudtam, szemem elborult, sem éltem, Se haltam és nem tudtam semmiről, A fény szívébe néztem csak, a csöndbe. 40 Öd' und leer das Meer.

Madame Sosostris, híres jósnő, Náthás volt, mindazonáltal Európa legokosabb asszonyának Számít bűnös kártyáival. Íme, úgymond, Az ön lapja, a vízbefúlt Föníciai Tengerész, (Gyöngyök a szeme helyén, nézze csak!) Ez meg a Sziklák Hölgye, Belladonna, A helyzetek hölgye. 50 Itt az ember a három bottal, és ez a Kerék, És ez a félszemű kalmár, és ezt a letakart Kártyát viszi a hátán, s nem szabad Megnéznem. Hol van az Akasztott Ember? Vízbefúlástól óvakodjék. Rengeteg embert látok, körbejárnak. Köszönöm. Üdvözlöm a kedves Equitone-nét: Magam viszem neki a horoszkópot – Manapság annyira vigyázni kell.

Valószerűtlen város, 60 A téli virradat barna ködében A London Bridge-en a tömeg tolongva jár, Nem tudtam, mily sokat tiport el a halál. A légbe nyögve kurta sóhajok, S járta tömeg, lábuk elé tekintve, A dombra föl s le a King William Streetre, Hol a Saint Mary Woolnoth nagyharangja Holt hanggal üti a végső kilencet. Ismerőst láttam és szóltam kiáltva: „Stetson! Együtt voltunk Mylaenél a hajókon! 70 Hullát ültettél múlt évben a kertben – Kihajt-e? Lesz-e még idén virága? Vagy ártott tövének a hirtelen fagy? Űzd el a Kutyát, az ember barátját, Vagy körmei a földedből kiássák! Te! hypocrite lecteur! – mon semblable – mon frére!”

II Egy sakkparti

Egy széken ült, mint fénylő trónuson, Márványon izzó széken, oszlopok Borága mögül arany Cupido Lesett (szemét szárnyába dugta a másik), 80 S oszlopokon az üveg kétszerezte Lángját hétágú kandelábereknek, S az asztalra vetett fényt, mely a nő Selyemtokokból bőven áradó Ékszerszikrázásába ütközött; Nyitott elefántcsont s szines üveg Fiolákból kenőcsbe, porba, vízbe Kevert orv illatjai felkavarták S szagokba fojtották az észt; az ablak Felől fuvó lég felbolygatta őket, 90 És zsírjuktól a megnyúlt gyertyalángok Füstje feltört a laqueariára S a mennyezet kockáit szétzilálta. Rézzel táplált nagy tengermélyi fa A tarka kőkeretben zölddel s naranccsal égett, S e bús fényben faragott delfin úszott. Az ódon kandalló fölött akárha ablak Mutatná erdei színhelyen Philomelát, Ki barbár király vad kényszere elől Átváltozik; mégis a csalogánynak 100 Egész pusztát betölt a hangja sérthetetlen, S még mindig űzi a világ, de ő csak Csattog piszkos fülekbe. S az időnek más elhalt csonkjai A falra írvák; meredő, Ágaskodó ábrák juháztatták a termet. Lépcsőn csoszogó léptek. A tűz fényében, a kefe alatt haja Tűzfoltokban terült szét, Szavakra izzott, majd elnémult vadul. 110

„Ma ideges vagyok. Maradjon itt. Beszéljen. Soha nem beszél. Beszéljen. Mire gondol most? Mit gondol? Sosem Tudhatom. Gondoljon, amit akar.”

Azt gondolom, patkány-közben vagyunk, Itt vesztek el a holtak csontjai. „Hallja? Mi az?" A szél a küszöbön. „És most? Mi ez? Mit művel ez a szél?" Semmit most újra semmit. 120 „Maga Semmit se tud? Semmit se lát? Semmire sem Emlékszik?"

Emlékszem, Hogy gyöngyök a szeme helyén. „Él-e maga? Nincs semmi a fejében?" Csak Ó Ó Ó Ó e sekszpihíri Kóc Oly kikent-kifent Oly intelligens 130 „És mit tegyek most? Mit tegyek? Így rohanok ki, így megyek végig az utcán, Kibontott hajjal. És holnap mit tegyünk? És mindig mit tegyünk?" Tízkor meleg víz. És ha esik, négykor egy csukott autó. S játszunk egy parti sakkot, S csupasz szemgolyónkat nyomorgatván várjuk, hogy kopognak az ajtón. Mikor leszerelt a Lili ura, mondtam – Nem kerteltem, megmondtam a szemébe, 140 ZÁRÓRA URAIM Most Albert hazajön, hát adj magadra egy kicsit. Kíváncsi lesz, hová tetted a pénzt, amit fogakra Adott. Ott voltam, mikor adta. Mindet Huzasd ki, Lil, és új fogsort csináltass, Azt mondta, így nem bírok rád se nézni. S nem bírok én sem, gondolj szegény Albertre, mondtam, Katona volt négy évig, most mulatni szeretne, S ha veled nem lehet, lesz, akivel lehetne, mondtam. Úgy? Lesz? – azt mondta. úgy szokott lenni, mondtam. 150 Tudom, kinek köszönjem, mondta, s rám nézett erősen. ZÁRÓRA URAIM Ha nincs kedved hozzá, azt mondtam, hagyd csak így. Lesz akinek kell, ha neked nem. De ha Albert leráz, ne mondhasd, hogy én nem szóltam neked. Szégyelld magad, mondtam, hogy ilyen régiség vagy. (Mert Lili csak harmincegy éves.) Mit csináljak, azt mondta lógó orral, A piruláktól van, hogy elhajtsam őket, azt mondta. (Öt volt már neki, s majd meghalt a kicsi George-tól.) 160 A patikus azt mondta, rendbe jövök, de már nem vagyok az, aki voltam. Kész bolond vagy, mondtam neki. S ha Albert majd nem hagy békét neked, azt mondtam, ott tartasz megint. Mért mentél férjhez, ha nem kell gyerek? ZÁRÓRA URAIM S vasárnap Albert hazajött, meleg sonkát ebédeltek, Behívtak engem is, hogy a javát forrón együk — ZÁRÓRA URAIM ZÁRÓRA URAIM Jójszakát, Bill. Jójszakát, Lou. Jójszakát, May. Jó éjszakát. 170 Pá, Pá. Jó éjt. Jó éjt. Jójszakát, hölgyeim, Jójszakát, drága hölgyeim, jó éjszakát, jó éjszakát.

III Tűzbeszéd

A folyó sátra szétszakadt, utolsó levél-ujjak Mélyednek be a nedves partba. Szél fut A barna földön nesztelen. Elköltöztek a nimfák. Csak csöndben, édes Temze, míg dalomat bevégzem. Nem visz a folyó üres üveget, uzsonnapapírt, Selyemzsebkendőt, kartondobozt vagy cigarettacsutkát, Se nyári éjek más tanújelét. Elköltöztek a nimfák. S barátaik, a bankigazgatóknak naplopó sarjai 180 Elköltöztek, címük se hagyva hátra. Ültem és sírtam a Genfi-tó vizeinél... Csak csöndben, édes Temze, míg dalomat bevégzem, Csak csöndben, édes Temze, nem leszek hangos én sem. De mögöttem, hallom, hideg huzat, Csontzene közeleg, s a kuncogás fültől fülig hasad. A tenyészeten át patkány lopódzott S a parton vonszolta nyálkás hasát, Míg én a gáztartály körül egy téli estén Halásztam a szürke csatornavízben 190 S király-bátyám vízbevesztén tünődtem S király-apámon, ki előtte halt meg. Csupasz, fehér testek a puha marton, Csontok, száraz üregbe dobva - Csak patkányláb zörrenti évről évre. De mögöttem hallom közelebb érve Autókürtök hangját – Sweeney is azzal Indul majd Porternéhoz a tavasszal. Porternét a holdsugarak beragyogták Lánya is ott állt 200 Lábukat szódavízbe mossák Et O ces voix d'enfants, chantant dans la coupole!

Fid fid fid Csek csek csek csek csek csek Tereus Vad kényszere.

Valószerűtlen Város Egy téli délután barna ködében Eugenides úr, a szmirnai kalmár Borotválatlanul, zsebében mazsola 210 C. i. f. London: okmányai látra, Meghívott zagyvalék franciasággal Villásreggelire a Cannon Street Hotelbe, Aztán weekendezni a Metropole-ba. A lila órán, mikor a szem, a hát Az íróasztaltól felkél, mikor az emberi masina vár, Mint taxi vár zihálva, Én, vak Tiresias, ráncos asszonyi mellem, Vénember, ki két élet közt zihál, De látom a lila esti órát, amelyben. 220 A hajós a tengerről hazaszáll, Haza a gépírónő teára, reggelijét Leszedi, begyújt, nyit konzerveket – Ablakából kilógnak száradó Kombinék, melyeket az alkonyati fény ver, Díványán (éjjel ágy) még egy csomó Hever: papucs, leibchen, harisnya, míder. Én, Tiresias, ráncos csecsű vén Figyeltem ezt, s megjósoltam, mi jön még – Én is vártam, hogy jön-e már a vendég. 230 Már itt van, pattanásos, egy vigécnél Praxi, merész szemű fiatalember, Kisember, kin az önhittség úgy áll, mint Bradfordi milliomoson a cilinder. Az idő most, úgy sejti, kedvező: A lány evett, fáradt s unott utána, Elkezdi buzgón fogdosni – a nő Nem löki el, ha még nem is kívánja. Izgatott, elszánt, támad már rohamvást, Nincs, ami kutató kezét kivédi; 240 A hiúsága nem is vár viszonzást, És a közönyt már élvezetnek érzi. (És én, Tiresias, mindent, ami Ez ágy-díványon lett, előreéltem; Én, aki ültem Théba falai Alatt s bolyongtam holtak közt a mélyben.) Egy utolsó, fölényes csókot ad S a sötét lépcsőkön tapogatódzik...

Alig tud már a lezajlott kalandról A lány, megfordul, a tükörbe néz, 250 Homályosan egy percig arra gondol: „Túl vagyok rajta — ez volt az egész." Ha szépasszony mulat, s ha azután Szobájában maga marad borongva, Gépiesen végigsimít haján És föltesz egy lemezt a gramofonra.

„És jött felém egy hang a víz felől" Végig a Stranden és a Queen Victoria Streeten. Ó Város város, hallom néha még Egy kocsma mellett a Lower Thames Streeten, 260 Egy mandolin jóleső hangja nyávog, S belül zsivaj, ricsaj, hol a halászok Lebzselnek délben, és a Magnus Vértanú Templomban a falak Tündöklő jón fehér s arany rejtélyt sugárzanak.

Kátrány meg olaj A folyó verítéke Úsznak a bárkák Forduló dagállyal Vörös vitorla 270 Szárnyal A súlyos árbocfán szélvédte vidékre. Úsztatnak a bárkák Rönköket lefele Hol elmarad Greenwich El a Kutyák Szigete Vejjalala lejja Vallala lejjalala

Erzsébet és Leicester Itt evezett 280 Hajójuk tatja Aranyos kagyló Vörös meg arany Hirtelen habzó Két parton a csipke Délnyugati szél Lefelé vitte Harangok zúgása Fehérlő tornyok Vejjalala lejja 290 Vallala lejjalala

„Villamosok, poros fák közelében Highbury szült engem. Richmond és Kew Tett tönkre. Richmondnál egy szűk kenu Fenekén hanyatt felhúztam a térdem."

„Lábam Moorgate-nál, a szívem pedig Lábam alatt. Ő sírt az esemény Után. – Most új élet következik – Igérte. Nem szóltam. Mit bánom én!"

„Margate-i fövenyen. 300 Bennem nem él Semminek kapcsolata semmi. Repedt körmök a piszkos kezeken. Népem amit szerény népem remél A semmi," la la

És ekkor Karthágóba értem

Lángban lángban lángban lángban Ó Uram Te kitépsz engem Ó Uram Te kitépsz 310

Lángban

IV A vízbefúlás

Phlebas, a föníciai már kéthetes halott. Sirálykiáltozást, hullámverést már elfelejtett S a hasznot-veszteséget is. A tengermélyi áramok Susogások közt csontjaira leltek. Le-föl átringta mind az életkorokat És örvénybe jutott. Zsidó vagy? Bármi vagy, Te, ki kormánykerék mellett a szélbe nézel, 320 Lásd Phlebast, aki valaha szép szálas volt, mint te magad.

V Amit a mennydörgés beszél

Volt izzadt arcokon rőt fáklyafény Volt a kertekben fagyos némaság Volt halálkín fenn a kövek hegyén Ordítozás és sírás Börtön és palota s visszhangzó Tavaszi mennydörgés messzi hegyek közt Most már halott ő aki élt Mi akik éltünk meghalunk most Csak egy kis türelem 330

Itt nincsen víz itt csak szikla van Szikla van víz nincs van homokos út Az út fenn a hegyek közt kígyózik Sziklás víztelen hegyek között Ha volna víz hát inni megpihennél Sziklák közt csak megy az ember nem eszmél Szárazon izzadsz lábad a homokban Ha volna legalább víz a sziklák között Holt hegység szuvas fogú száj mely köpni képtelen Itt állni nem lehet s feküdni ülni sem 340 Még csöndesség sincs a hegyekben Csak szárazdörgés nem hoz esőt Még magányosság sincs a hegyekben Csak zord vörös arcok vicsorognak Vályogkunyhók ajtajában Ha volna víz S ne szikla Ha volna szikla És volna víz is És víz 350 Egy forrás Tó a sziklák között Ha csak hangja volna meg a víznek Ne csak tücsökhang S száraz fű szólna De víz csobogna sziklák között Hol remeterigó szól a fenyőfán Csip csöp csip csöp csöp csöp De víz sehol sincs

Ki megy melletted mindig harmadiknak? 360 Ha számolom csak te meg én vagyunk mi ketten De ha fölfele nézek a fehér uton Melletted mindig ott megy valaki más is Suhan csuklyásan, barna köpenyben Azt sem tudom férfi-e vagy asszony – De ki is az a másik oldaladon?

Mi ez a hang a légbe fenn Anyai sirámok mormolása Kik e csuklyás hemzsegő hordák Végtelen síkokon, repedt földön botolva 370 Határuk csak a lapos láthatár Mi ez a város a hegyek fölött Szétpattan s újul és a lila égbe foszlik Omló tornyok Jeruzsálem Athén Alexandria Bécs London Valószerűtlen

Egy nő kibontva hosszú éjhaját E húrokon hegedült halk zenéket S cincogtak lila fényen át 380 S csapkodtak csecsemőarcú denevérek S fejjel le kúsztak egy sötét falon S a légben fejtetőn álltak a tornyok S emlékező harangok szava kongott S hangok zengtek üres ciszternákból és kiszáradt kutakból.

A hegyek közt e beomlott üregben Fakó holdfényben, behorpadt sírok Fölött dalol a fű, a kápolna körül Üres kápolna áll, csak szél tanyája. Ablaka nincsen, ajtaja leng, 390 Nem árthat puszta csont. Csak egy kakas a szarufán Kukurikú, kukurikú. Villámfényben. Majd párás szélroham Esőt hozó

A Ganga leapadt, a lankadt levelek Esőre vártak, míg fekete felhők Gyűltek nagy messze, Himaván fölött. A dzsungel lelapult, görnyedve némán. Aztán a mennydörgés beszélt 400 DA Datta: és mit is adtunk? Barátom, vér rázza a szívemet Egy önfeledt pillanat vakmerése Mit a józanság kora se tud majd visszavonni Ettől léteztünk mi, és csakis ettől S ezt nem mondja el rólunk gyászbeszéd Se sírfeliratunk a jótét pókháló alatt Se végrendeletünk, melyet szikár ügyvéd kibont Üres szobánkban 410 DA Dajadhvam: hallottam a kulcs Fordul a zárban egyszer, csakis egyszer A kulcsra gondolunk, ki-ki börtönében Gondol a kulcsra, s börtönt létesít Ki-ki esténkint, éteri zajoktól Percnyi életre kel egy letört Coriolanus DA Damjata: Derűsen felel a csónak A kéznek, amely vitorlához evezőhöz ért 420 Nyugodt tenger volt, felelt volna szíved Derűsen a hívásra, dobogva engedelmesen Kormányzó kéznek

Ültem a parton Halásztam, a szikkadt síkság mögöttem Rendbe hozzam-e legalább a saját földjeimet?

London Bridge már leszakad leszakad leszakad

Poi s'ascose nel foco che gli affina Quando fiam uti chelidon – Ó fecske fecske Le Prince d'Aquitaine á la tour abolie 430 Romjaimat védem e törmelékkel Illek én hozzád. Hieronymo megint megőrült. Datta. Dajadhvam. Damjata.

Santih santih santih

Eliot jegyzetei az Átokföldjé-hez

E költeménynek nem csupán címét (The Waste Land), hanem a tervét és esetleges szimbolizmusának jó részét is Jessie L. Westonnak a Grál-legendáról szóló könyve sugalmazta: From ritual to romance (Cambridge). Való- jában oly sokkal vagyok adósa e könyvnek, hogy az sokkal könnyebben tisztázhatja a költemény nehézsé- geit, mint az én jegyzeteim; a könyv önálló érdekessé- gétől eltekintve, ezért ajánlom mindazoknak, akik úgy gondolják, hogy a költemény ilyesféle tisztázása meg- éri a fáradságot. Általánosabb éttelemben vagyok adósa egy másik antropológiai műnek, amely a mi nemzedékünkre mélységes hatással volt: a The golden bough-ra gondolok, különösen az Admis, Attis, Osiris két kötetének vettem hasznát. Mindazok, akik e mű- vekben jártasak, azonnal felismernek a költeményben bizonyos utalásokat a termékenységi szertartásokra.

I. A halottak temetése

20. sor Vö. Ezékiel H. 1. 23. sor Vö. Prédikátor XII. S. 31. sor L. Trisztán és Izolda I. 58. sor 42. sor L. ua. III. 24. sor 46. sor Nem ismerem pontosan a Tarot kártya összetételét, és szabadon el is tértem attól a magam céljainak megfelelően. Az Akasztott Ember kétféleképpen is illik a szándékom- hoz: mert gondolkodásomban összekapcso- lódik Frazer Akasztott Istenével; és mert összekapcsoltam az emmausi tanítványok útjának csuklyás alakjával is az V. részben. A Föníciai Tengerész meg a Kalmár később jelennek meg, akárcsak a „rengeteg ember", és a Vízbefúlás a IV. részben történik meg. Az Ember a Három Bottal (a tarot kártya hiteles lapja) nálam, teljesen önkényesen, a Halászkirályhoz kapcsolódik. 60. sor Vö. Baudelaire: „Fourmillante cité, cité pleine de réves, Oú le spectre en plein jour raccroche le pas- sant." 63. sor Vö. Inferno III. 55-57.: „si lunga tratta di gente, ch'io non avrei creduto che morte tanta n'avesse disfatta." 64. sor Vö. Inferno IV. 25-27.: „Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare, non avea piante ma' che di sospiri, che l'aura eterna facevan tremare." 68. sor Ezt a jelenséget gyakran megfigyeltem. 74. sor Vö. Webster: A fehér ördög-ének gyászdalával. 76. sor L. Baudelaire: A romlás virágai, Előhang.

II. Egy sakkparti

77. sor Vö. Antonius és Kleopátra, H. 2. 190. sor. 92. sor Laquearia. L. Aeneis, I. 726.: dependent lychni laquearibus aureis incensi, et noctem flammis funalia vincunt. 98. sor Erdei színhely. L. Milton: Elveszett paradi- csom, IV. 140. 99. sor L. Ovidius: Metamorphoses, VI. Philomela. 100. sor Vö. III. rész 204. sor. 115. sor Vö. III. rész 195. sor. 118. sor Vö. Webster: „Is the wind in that door still?" 126. sor Vö. I. rész, 37., 48. sor. 138. sor Vö. a sakkjátékkal Middleton Women beware women-jében.

III. A tűzbeszéd

176. sor L. Spenser: Prothalamion. 192. sor Vö. A vihar, I. 2. 196. sor Vö. Marvell: Rideg úrnőjéhez. 197. sor Vö. Day: Parliament of Bees: „When of the sudden, listening, you shall hear, „A noise of horns and hunting, which shall bring „Actaeon to Diana in the spring, „Where all shall see her naked skin..." 199. sor Nem ismerem annak a balladának az eredetijét, ahonnan ezeket a sorokat vettem: Sidneyből, Ausztráliából hozták nekem. 202. sor L. Verlaine: Parsifal. 210. sor A mazsola árába bele volt értve a szállítás és biztosítás Londonig, és a hajófuvarlevelet és egyéb okmányokat a látra szóló váltó kiegyen- lítése ellenében kellett a vevőnek kézbesíteni. 218. sor Tiresias, bár itt csak néző, nem pedig ,sze- replő", mégis a legfontosabb személyiség a költeményben, aki magában egyesíti mind a többit. Mint ahogy a félszemű kalmár, a ma- zsolaárus beleolvad a Föníciai Tengerészbe, és az utóbbi nem teljesen határolható el Ferdi- nánd nápolyi királyfitól, úgy minden asszony egy asszony, és a két nem Tiresiasban találko- zik. Amit Tiresias lát, az voltaképpen a költe- mény tartalma. A teljes részlet Ovidiusnál antropológiailag nagyon érdekes: "...Cum Junone jocos et »major vestra profecto est Quam, quae contingit maribus«, dixisse, »voluptas.« Illa negat; placuit quae sit sententia docti Quaerere Tiresiae: venus huic eras utraque note. Nam duo magnorum viridi coeuntia silva Corpora serpentum baculi violaveret ictu Deque viro factus, mirabile, femina seprem Egeret autumns; octavo rursus eosdem Vidít et »est vestrae si tanra potentia plagae«, Dixit »ut auctoris sortem in contraria muter, Nunc quoque vos feriam lo percussis anguibus isdem Forma prior rediit genetivaque yenit imago. Arbiter hic igitur lumptus de lite jocose Dicta Jovis firmai; gravius Saturnia justo Nec pro materig fertur doluisse suique Judicis aeterna damnavit lumina nocte, At pater omnipotens (neque enim licet inrita cuiquam Facta dei fecisse deo) pro lumine adempto Scire futura dedit poenamque levavit honore."

221. sor Ez talán kevésbé pontosnak látszik, mint Sappho sorai, de én a lapos csónakon járó, part menti halászra gondoltam, aki hazatér éj- szakára. 253. sor L. Goldsmith: Dal A wakefieldi lelkész-ből. 257. sor L. A vihar, m. f. 263. sor A Szent Magnus Vértanú templom számomra egyike Wren legszebb belső kiképzéseinek. L. The proposed demolition of nineteen city churches (P. S. King and Son, Ltd.). 266. sor Itt kezdődik a három Temze-lány éneke. A 292-306. sorban felváltva beszélnek. L. Is- tenek alkonya III. 1: A Rajna-lányok. 279. sor L. Froude: Erzsébet, I. kötet, 4. fej., De Quadra levele Fülöp spanyol királyhoz: „A délutánt egy bárkán töltöttük és a játéko- kat néztük a folyón. (A királyné) egyedül volt Lord Roberttel és velem a hajó tatján, amikor elkezdtek összevissza fecsegni, sőt odáig me- részkedtek, hogy Lord Robert végül azt mondta jelenlétemben, hogy semmi ok sincs rá, miért ne házasodnának össze, ha ez a ki- rálynőnek kedvére való." 293. sor Vö. Purgatorio, V. 133.: „Ricorditi di me, che son la Pia; „Siena mi fe', disfecemi Maremma." 307. sor L. Szent Ágoston Vallomásait: „és ekkor Karthágóba értem, ahol a tisztátalan szerel- mek katlana töltötte be fülemet énekével." 308. sor Buddha Tűzbeszédjének teljes szövege (amely fontosságában megfelel a Hegyi Beszédnek) – mert onnan valók e szavak – megtalálható fordításban néhai Henry Clarke Warren Buddhism in Translation-jában (Harvard Oriental Series). Warren egyike volt Nyugaton a budd- hista tanulmányok nagy úttörőinek. 309. sor Ismét Szent Ágoston Vallomásai-ból. A keleti és nyugati aszkétizmus e két képviselőjének összekapcsolása, mint a költeménye részének betetőzése – nem véletlen.

V. Amit a mennydörgés beszél

Az V. rész kezdete három témát dolgoz fel: az utat Emmausba, a közeledést a Veszélyes Kápolnához (lásd Jessie Weston könyvét) és Kelet-Európa jelenlegi ha- nyatlását. 357. sor Ez a Turdus aonalaschkae pallasii, a remeterigó, melyet én Quebec tartományban hallottam. Chapman azt mondja (Észak-Kelet-Amerika madarainak kézikönyve) : „magányos erdőségek- ben és sűrű bozótokban leginkább honos... Éneke nem a változatosságáért vagy teltségé- ért figyelemre méltó, hanem a hang tisztasá- gában, édességében és finom árnyaltságában páratlan." Méltán híres a „csörgedező dalolása". 360. sor A következő sorokat egy délsarki expedíció- nak (már elfelejtettem, hogy melyiknek, de azt hiszem, Shackleton valamelyik felfedező útja volt) a története ihlette: arról szólt, hogy a kutatók, erejük végső határán, abban az ál- landó tévképzetben éltek, hogy eggyel többen vannak, mint amennyit össze tudtak számolni. 367-77. sor Vö. Hermann Hesse: Blick ins Chaos: „Schon ist halb Europa, schon ist zumindest der halbe Osten Europas auf dem Wege zum Chaos, fährt betrunken im heiligen Wahn am Abgrund entlang und sings dazu, sings bet- runken und hymnisch wie Dmitri Karamasoff sang. Ober these Lieder Jacht der Bürger be- leidigt, der Heilige und Seher hört sie mit Tränen." 402. sor Vö. „Datta, dajadhvam, damjata" (Adj, érezz együtt, irányíts). A Mennydörgés jelentésének meséje megtalálhatóa Brihadaranjaka–Upani- sad, 5. L-ben. A fordítás lelőhelye Deussen: Sechzig Upanishads des Veda, 489. o. 408. sor Vö. Webster: A fehér ördög, V. 6.: Férjhez megy, mielőtt Kikezdené a féreg szemfedőd S a pók beszőné sírfeliratod... (Mészöly Dezső ford.) 412. sor Vö. Inferno XXXIII. 46.: „ed io senti chiavar Fuscio di sotto all' orribile torte." Hasonlóképpen Bradley: Látszat és valóság, 346. o.: „Külső érzékeléseim nem kevésbé egyediek, mint gondolataim és érzéseim. Tapasztalásom mindkét esetben saját körömön belül marad, és ez a kör kívülről be van zárva; és, bár minden eleme hasonló, valamennyi szférája fényáthatlan a környező szférák számára... Egyszóval, a lélekben megjelenő létezésként tekintve, az egész világ mindenki számára önlelkének egyedi sajátossága." 425. sor L. Weston: From Ritual to Romance, a Ha- lászkirályról szóló fejezet. 428. sor L. Purgatorio XXVI. 148.: , „Ara vos prec per aquella valor „que vos guida al som de Pescalina „sovegna vos a temps de ma dolor." Poi s'ascose nel foco che gli affina.' 429. sor L. Pervigilium Veneris. Vö. Philomelával a II. és III. részben. 430. sor L. Gérard de Nerval szonettje: El Desdichado. 432. sor L. Kyd: Spanyol tragédia. 434. sor Santih. Ismételve, mint ezen a helyen, egy Upanisad szertartásos befejezése. Jelentését mi körülbelül igy tudnók kifejezni: „A béke, mely meghaladja a megértést."

|