Kipling, Rudyard: The Jungle Books (detail)

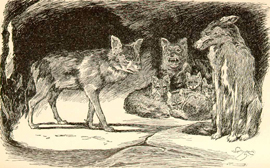

The Jungle Books (detail) (Angol)Now Rann the Kite brings home the night That Mang the Bat sets free-- The herds are shut in byre and hut For loosed till dawn are we. This is the hour of pride and power, Talon and tush and claw. Oh, hear the call!--Good hunting all That keep the Jungle Law! "Augrh!" said Father Wolf. "It is time to hunt again." He was going to spring down hill when a little shadow with a bushy tail crossed the threshold and whined: "Good luck go with you, O Chief of the Wolves. And good luck and strong white teeth go with noble children that they may never forget the hungry in this world." He scuttled to the back of the cave, where he found the bone of a buck with some meat on it, and sat cracking the end merrily.

|

A Dzsungel Könyve (részlet) (Magyar)Csil keselyűnk éjt hoz nekünk, Meng küldi, a bőregér - Tető alatt a házi dal, s a mi fajtánk szerte-tér: az éj az időnk, zsákmányol erőnk, karmunk prédát kerít. Sikert neked, ha tiszteled a Dzsungel Törvényeit! Éji dal a Dzsungelben

- Aúuh! - szólalt meg Farkas apó - Ideje már, hogy vadászni induljak. Éppen le akart rohanni a domb oldalán, amikor egy lompos farkú kis árnyék jelent meg a küszöbön, s azt nyivákolta: - Jó szerencse járjon veled, Farkasok Fejedelme! Jó szerencsét és erős fogakat kívánok dicső gyermekeidnek is, hogy sohase feledkezzenek meg azokról, akik éheznek ezen a világon. A sakál volt az, az Élősködő Tabaki. Az indiai farkasok megvetik Tabakit, mert mindig rosszban sántikál, pletykát hordoz, és húscafatokat meg bőrdarabokat kurkász fel a falusi szemétdombokon. De azért félnek is tőle a farkasok, mert Tabaki könnyen megvész, könnyebben, mint akárki más a vadonban. Olyankor aztán elfelejti, hogy valaha félt valakitől, végigszáguld az erdőn, s megmar mindenkit, aki az útjába kerül. Még a tigris is elfut, elbújik, ha a kis Tabaki megvész, mert a veszettség a legszörnyűbb dolog, ami vadállatot érhet. Az emberek tudós szóval "víziszonynak" nevezik az ilyesmit, de az állatok "devani"-nak, őrjöngésnek mondják, és menekülnek előle. - Hát gyere be, és nézz körül - mondta barátságtalanul Farkas apó -, de itt egy falás nem sok, annyi ennivaló sincs. - Nincs ám, farkasnak - felelte Tabaki -, de olyan hitvány kis teremtésnek, mint én vagyok, jó lakoma a száraz csont is. Nem arra születtünk mi, a Gidur-log, a sakálnépség, hogy kényeskedjünk, válogassunk. Besompolygott a barlang hátsó részébe. Megtalálta egy őzbak csontját. Volt valami kis hús is rajta, s boldogan nekiült, hogy megropogtassa ezt a maradékot. - Köszönöm szépen a megvendégelést - mondta a száját nyalogatva. - Milyen szépek ezek a dicső gyermekek! Milyen nagy a szemük! Már ilyen kicsi korukban! Igaz, igaz: eszembe juthatott volna, hogy királyok gyermekei már kiskorukban is felnőttek. Persze, Tabaki éppen olyan jól tudta, mint akárki más, hogy káros dolog az, ha gyerekeket szembe dicsér valaki; hízott a mája, hogy Farkas anyó és apó nyugtalannak látszottak. Tabaki csöndesen üldögélt, és örült a hitványságnak, amit elkövetett; aztán rosszindulatúan megjegyezte: - Sir Kán, a Nagy, elhagyta régi vadászterületét. Jövő hónapban ezek közt a dombok közt szándékozik vadászni, azt mondta nekem. Sir Kán a tigris volt, aki húszmérföldnyire onnét, a Vengunga folyó partján lakott. - Ahhoz nincs jussa! - szólalt meg haragosan Farkas apó. - A Vadon Törvénye szerint nincs joga kellő figyelmeztetés nélkül máshová költözni. Tíz mérföldnyi környéken elriaszt minden vadat, márpedig nekem mostanában kettő helyett kell vadásznom. - Nemhiába nevezte az anyja Lungrinak, Bénának - mondta csöndesen Farkas anyó. - Egyik lába születésétől fogva béna. Ezért nem tudott mással boldogulni, csak szarvasmarhával. Így aztán a Vengunga mentén lakó parasztok megharagudtak rá, s most idejött, hogy a mi parasztjainkat is megharagítsa. Tűvé teszik majd érte az erdőt, amikor messze jár, nekünk meg menekülni kell a gyerekeinkkel, ha felgyújtják a füvet. Igazán nagyon hálásak lehetünk Sir Kánnak! - Elmondjam neki, hogy milyen hálásak vagytok? - kérdezte Tabaki. - Takarodj innét! - ordított rá Farkas apó. - Takarodj, és eredj vadászni a gazdáddal! Itt már egy estére éppen elég bajt csináltál. - Megyek - mondta nyugodtan Tabaki. - Már halljátok is Sir Kán szavát odalenn a bozótban. Kár is volt fáradnom a hírhordással. Farkas apó fülelni kezdett, s a kis folyó felé futó völgyben hallotta is a tigris száraz, haragos, morgó, egyhangú üvöltését. Kiérzett belőle, hogy a tigris nem akadt zsákmányra, s nem bánja, ha az egész vadon megtudja ezt. - Adta bolondja! - mondta Farkas apó. - Ilyen lármával fogni éjjeli munkához! Hát azt hiszi ez, hogy a mi őzbakjaink is olyanok, mint azok a kövér Vengunga-parti szarvasmarhák? - Csitt! - mondta Farkas anyó. - Nem szarvasmarhára vadászik ez ma, nem is őzbakra, hanem emberre. Az üvöltés valami dongó kurrogássá változott, nem lehetett tudni, merről hallatszik. Az a hang volt ez, amely néha úgy megriasztja a szabad ég alatt háló favágókat és cigányokat, hogy egyenest a tigris torkába rohannak. - Emberre! - mondta Farkas apó, valamennyi fehér fogát megmutatva. - Hm! Hát nincs elég bogár és béka a víztartókban, embert kell neki enni, méghozzá a mi földünkön?! A Dzsungel Törvénye, amelynek egyetlen parancsa sem ok nélkül való, minden vadállatnak megtiltja, hogy embert egyék, kivéve, ha azért öli meg, hogy gyermekeit megtanítsa az ölés mesterségére. De akkor is a maga csapatának vagy törzsének vadászterületén kívül kell rá vadászni. Igazi oka pedig ennek a tilalomnak az, hogy az emberölés után, előbb vagy utóbb, fehér emberek jönnek elefántháton, puskával és száz meg száz barna ember gongokkal, rakétákkal, fáklyákkal. Ezt minden teremtett állat megsínyli a vadonban. Maguk közt azonban azt mondják okul a vadállatok, hogy az ember a leggyöngébb, legvédtelenebb teremtés a világon, hát nem dicsőség legyőzni. Mondják azt is - és ez igaz -, hogy aki embert eszik, megrühösödik, és kihull a foga. A kurrogás hangosabbra vált, s a végén teli torokkal harsant fel az "Ááá", az ugrásra készülő tigris kiáltása.

|

||||||||||||